Still a Thrill: Ballroom as Resistance

Written by La B. Fujiko

Written by La B. Fujiko

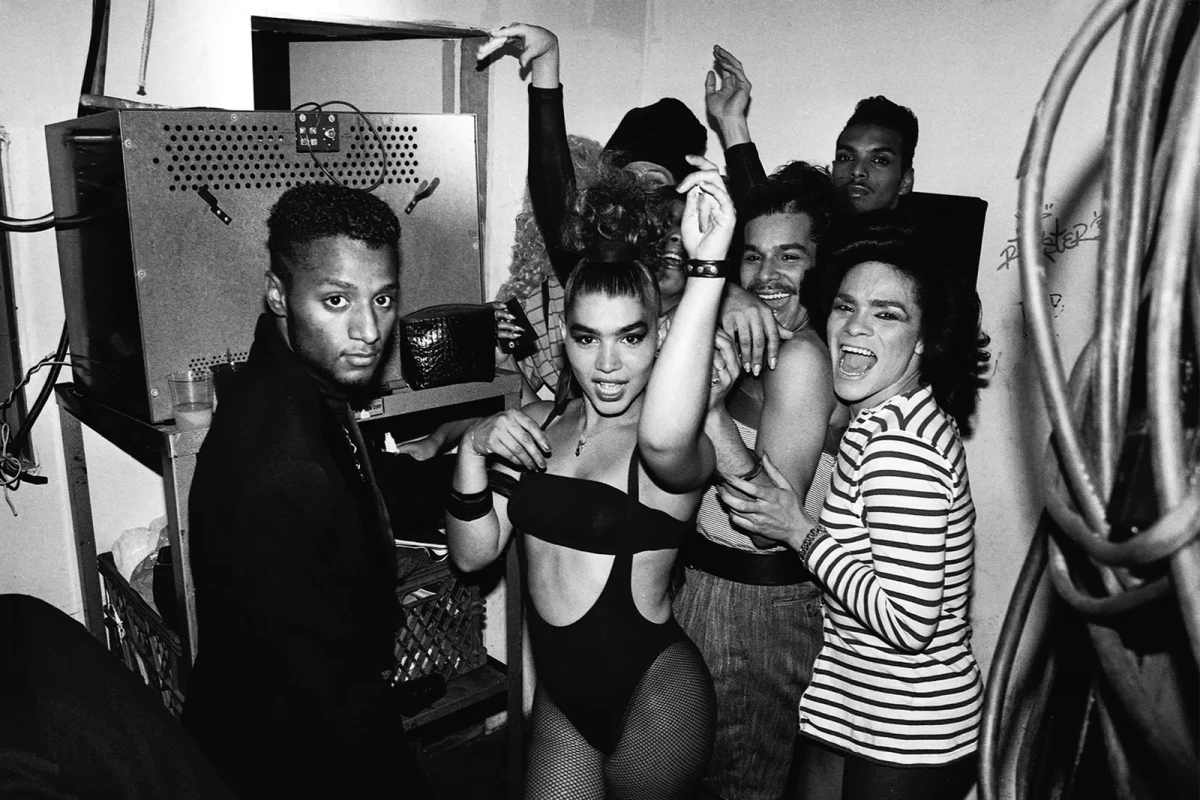

Ballroom was born in New York’s Black and Latinx LGBTQ+ community in the 1970s, at a time when survival often meant creating your own spaces of care, resilience, and resistance. Houses became chosen families, offering not only creativity and performance, but also protection, guidance, and solidarity.

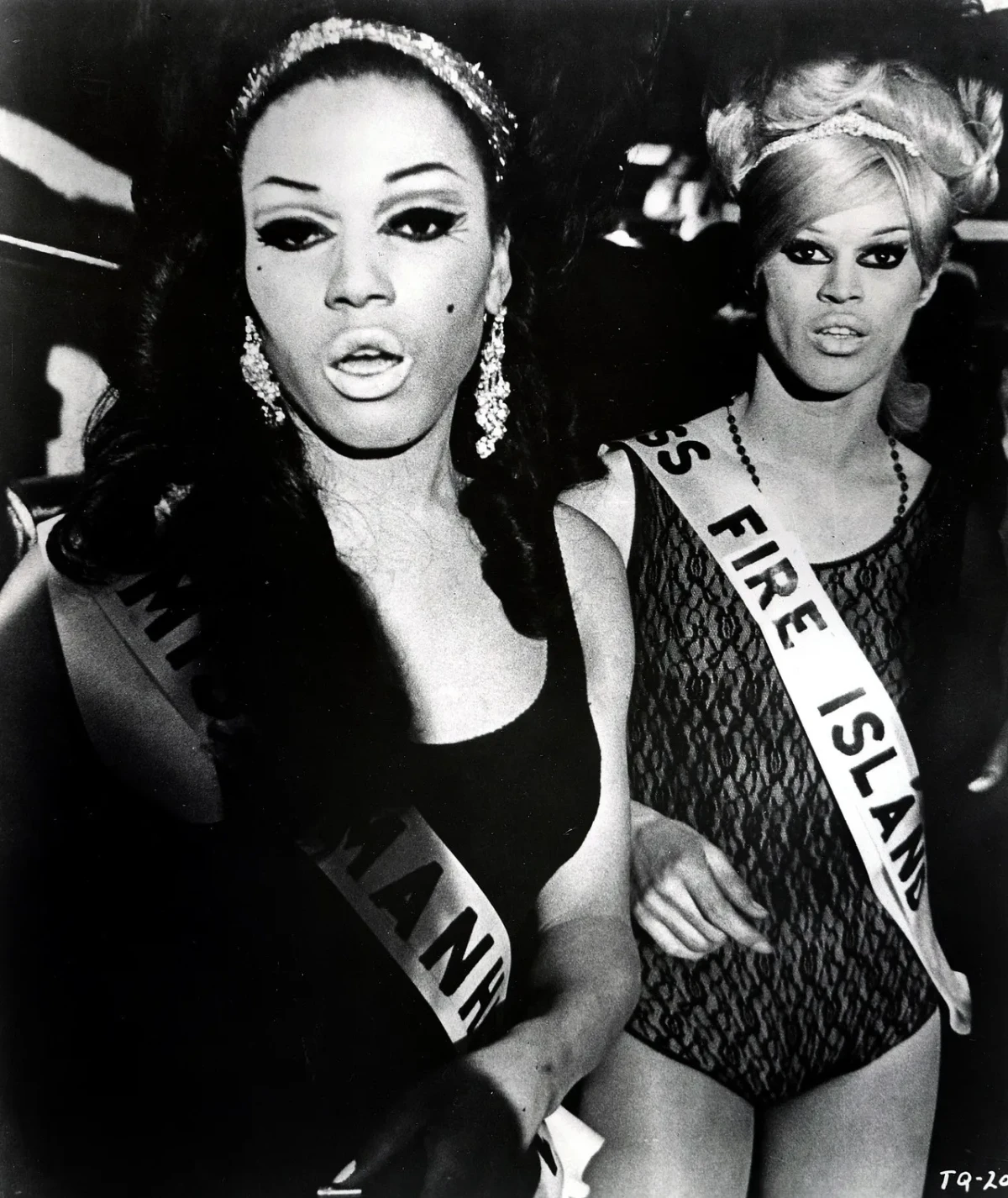

This story begins in New York, when drag balls were spaces of freedom and disguise. But even then, racism was present. In the 1960s, Black and Latinx queens were excluded from receiving prizes and discriminated against. Tired of being ignored, Crystal LaBeija walked off the stage of a ball in anger; from that gesture, in 1972, the House of LaBeija was born, the first house of ballroom. From then on, Houses would become networks of support, creative spaces, and alternative communities.

The 1968 documentary The Queen captured this turning point, showing Crystal’s walkout and her critique of racism in drag pageants. That moment crystallized a new beginning for ballroom: no longer just imitation of white beauty standards, but the creation of a culture rooted in Black and Latinx experience.

The ballroom scene originated within the Black and Latinx LGBTQ+ community in New York during the 1970s and 1980s. In a deeply hostile and violent social and political environment, this community became a space of survival, refuge, and empowerment. Within this context, Houses were chosen families that offered psychological, logistical, and financial support to countless young people who had been rejected by their biological families, had no future prospects, and often lacked self-love.

“Father” who guide and care for the “kids”. In addition, some Houses also include other roles such as “Prince/Princess”, “Godmother/Godfather”, ecc.

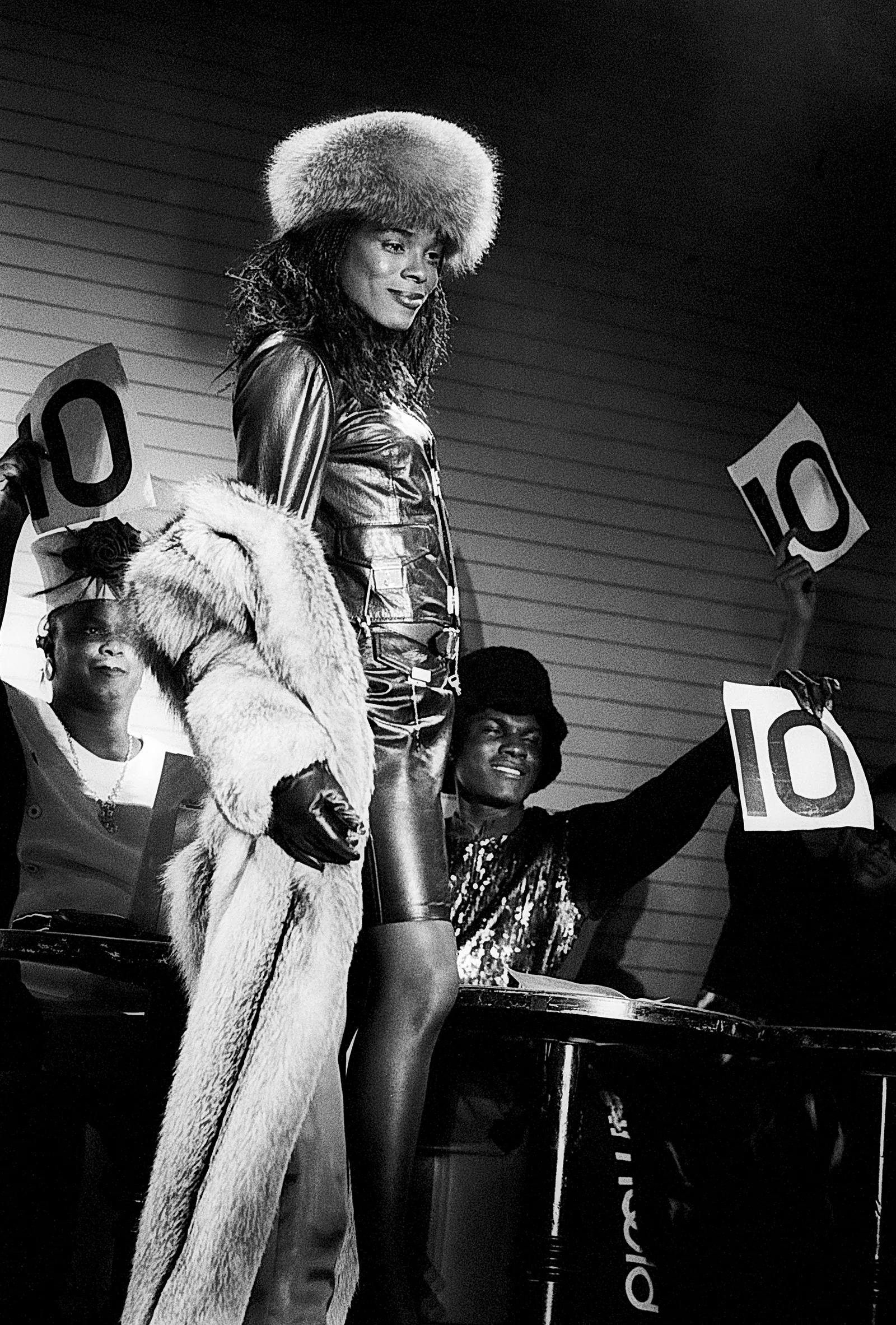

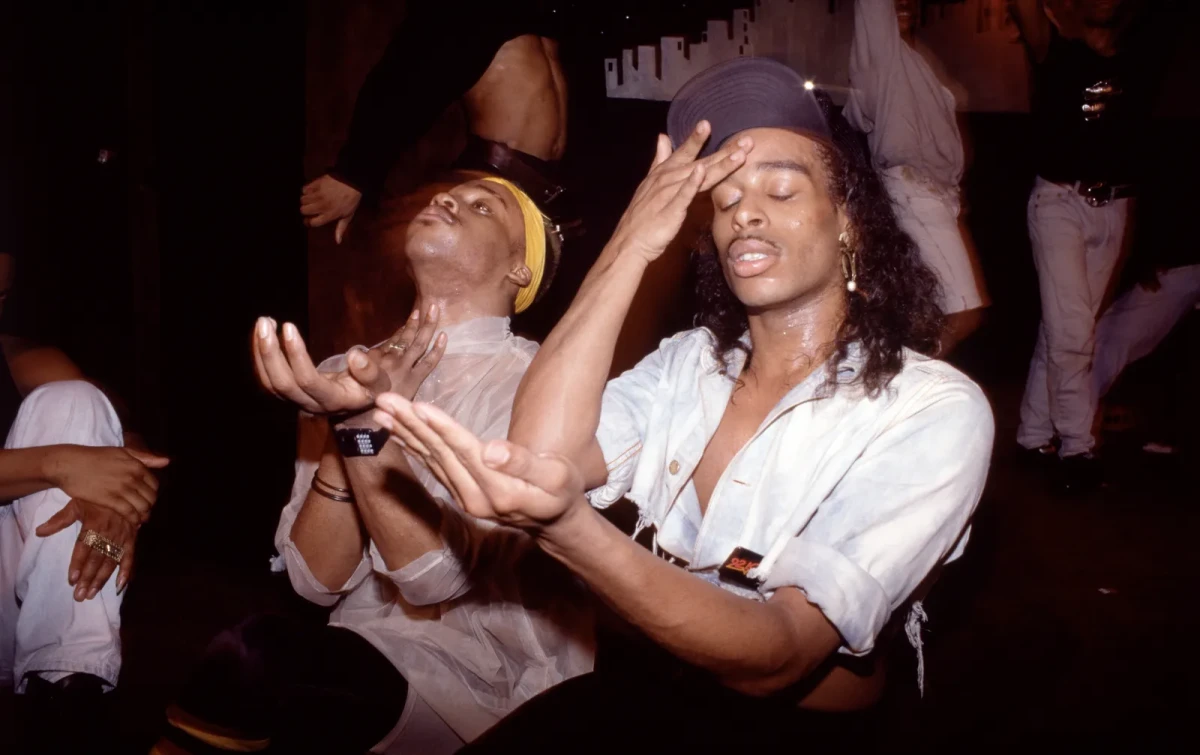

The Houses organized Balls, competitions of dance, style, and beauty, where participants could compete by creating outfits and performances inspired by fashion and celebrity. At these events, fantasies otherwise unattainable in everyday life could be lived out. People competed in categories before a panel of judges, accompanied by DJ and commentators.

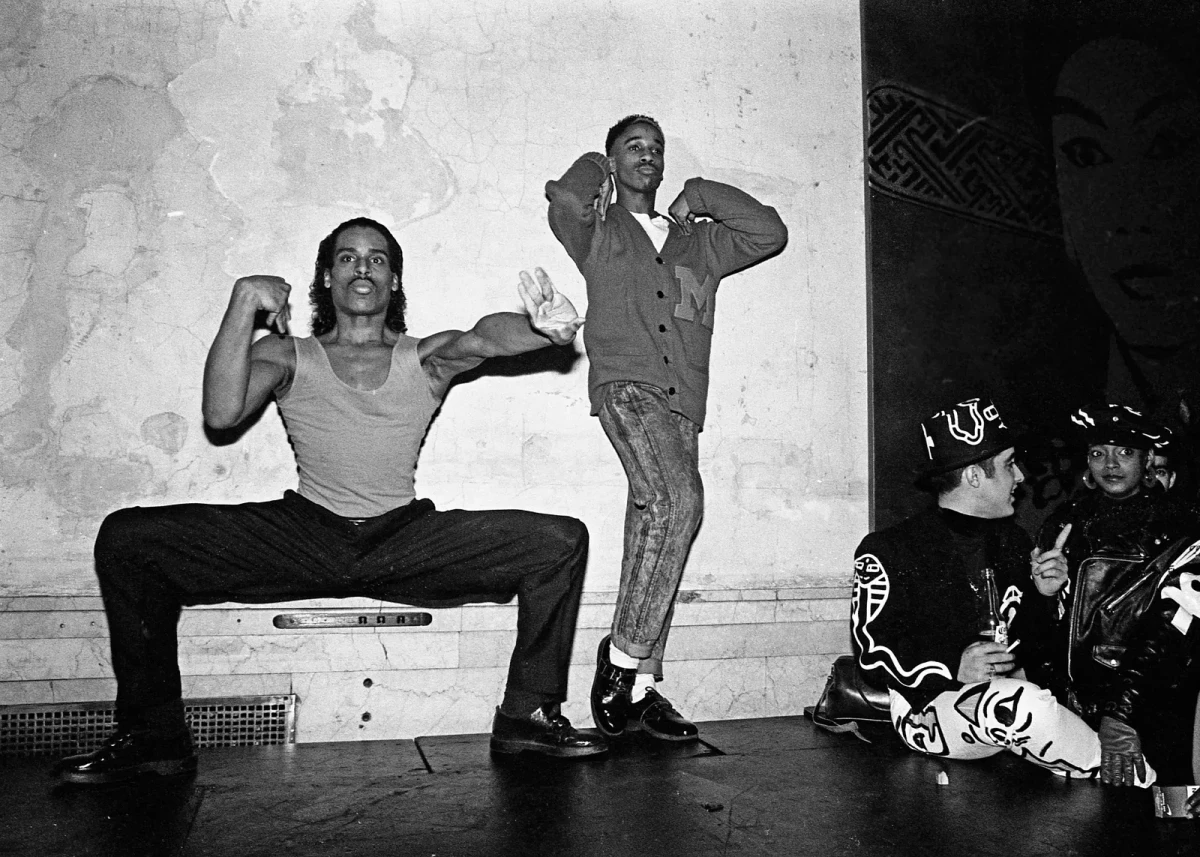

Voguing is the word that encompasses all the dance categories within the scene. Originally inspired by the poses of fashion magazines, it evolved over the years, and today we have three main categories: Old Way, danced to disco music, where the body creates lines, poses, and geometries, with references to the pop culture of the 1970s and 1980s, the moment when voguing began; New Way, danced to house music, where poses and geometric movements are accelerated and combined with contortionism; and Vogue Fem, extremely feminine and today the most popular style, with spins and dips that have become iconic, gone viral on social media, and been imitated in countless contexts.

The categories reflected both dreams and realities: Realness tested the ability to “pass” as cis and/or heterosexual in mainstream society; Runway celebrated attitude and style; Face focused on beauty and presentation; Body and Sex Siren highlighted confidence and sex appeal. These were not just competitions, but political acts that redefined the meaning of identity. Ballroom was not entertainment: it was survival transformed into art.

The judging system is based on tens and chops. When a participant walks a category, each judge evaluates whether they meet the requirements of that category. If the judge approves, they give the walker a ten, meaning they may continue to the next round. To advance, a participant must receive tens from all the judges at the panel. If a judge feels that the participant does not fulfill the category, they give a chop. A single chop means the walker is out of the competition. Afterwards, one-on-one battles take place until only a single winner of the category remains, and then the ball moves on to the next one. The judging is about meeting the elements required by each category, the quality of the presentation to the judges, and a look that respects the theme of the ball.

In ballroom, beyond trophies, recognition comes through a community built royalty system that honors experience and impact. Titles such as Legend, Icon, Pioneer or Trailblazer mark the legacy and influence of those who have shaped the scene.

From New York, ballroom spread across the United States. Houses became networks of care, solidarity, and growth. In the 1990s, the documentary Paris Is Burning brought visibility to this world, immortalizing icons such as Dorian Corey, Pepper LaBeija, Venus Xtravaganza and Willi Ninja. The film sparked both fascination and criticism.

Both within and outside the ballroom community, many did not recognize it as truly representative of the scene. Some of the very figures featured in the film declared that they never benefited from its success. At the same time, however, it gave us images of moments we would never have been able to witness otherwise, and it made famous important members of the scene who, sadly, passed away soon after.

Writer and activist bell hooks highlighted this ambiguity, noting that the film offered visibility but through a white, external gaze that risked turning lives of struggle into spectacle. Ballroom, she argued, could not be understood only as entertainment, but as a form of resistance born from race, class, and gender oppression.

At the same time, philosopher Judith Butler saw in ballroom the embodiment of her theory of gender performativity: the idea that gender is not something we are, but something we do, repeatedly, in acts that can subvert norms. Categories such as Realness make this visible, showing how identities are staged, questioned, and reinvented.

Ballroom has always lived in this tension between visibility and exploitation, performance and politics, survival and legacy. What began as a refuge became a global cultural force, proving that a community born at the margins can resist erasure, claim its own stage, and inspire the world.

The Iconic House of Ninja is one of the most renowned and influential houses in ballroom history. It was founded in New York in 1982 by Willi Ninja, often called the “Godfather of Voguing.” Willi brought voguing from the piers and ballrooms into the mainstream, performing with artists like Madonna and modeling on international runways, while never abandoning the roots of his community. The House of Ninja carried his vision forward: discipline, precision, and artistry combined with care, family, and resilience. Over the years, the House has expanded across continents, with chapters from Asia to Europe, and from South America to Russia. Members of the House of Ninja are known not only for their mastery in performance, but also for their commitment to keeping ballroom a space of resistance and love. To join the House of Ninja is to inherit a legacy: a responsibility to honor Willi’s dream of making voguing visible worldwide, while nurturing the next generations within the ballroom community.

Icon Milton Ninja recalls: “I started in Ballroom in Summer 1984, NYC and first walked the Adonis Ball in Midtown 43. Ballroom has shaped my life and helped me develop my personal sense and pride in being a gay Puerto Rican man at 55 years of age”. When the House of Latex closed, Milton joined the House of Ninja: “For me it was like being born again. Voguing gave me the lines, the precision, the beauty to show myself to the world”. His categories, Legendary Old Way and New Way, became extensions of his own identity.

Icon Javier the Dragon, entered the scene in 2000 after first encountering voguing at the Christopher Street piers in New York the previous year: “I saw voguing for the first time at the piers next to the West Side Highway in 1999 in NYC. I started ballroom in 2000 when I met Willi Ninja.” He became Willi Ninja’s last prodigy: “After he passed in 2006 I promised him I’d continue his dreams of making vogue worldwide known, and that’s exactly what I’m doing to this day.” For Javier, ballroom was more than dance: “Ballroom to me helped shape me to be the person I am today. It gave me a safe place where I could be myself. A place where I learned to have a backbone and to grow a tough skin, because, you know, people in the world are not always nice to us.” Ballroom, he says, teaches you to love yourself, to be creative, to find your chosen family. It gives you confidence and a support network when you don’t have it at home. His category, New Way, is a statement of discipline and artistry: “It is about geometric shapes with your body, with perfectly precise lines, grace, and flexibility.”

Legendary Nando Ninja, from Florida, found ballroom in 2001: “My ballroom journey began in Miami, Florida in 2001 at the ‘Boys 2 Boys’ youth group meetings. It was there that I first connected with the community that would change my life.”Having grown up in a religious household, he eventually lost the bonds with his biological family, and ballroom became his refuge: “Ballroom became my lifeline—a space where I could connect with others who were Queer and Gay like me.” In 2002, he was invited to become a founding member of the Miami Chapter of the House of Ninja: “I truly found my path.” Through ballroom, Nando found his chosen family—people who guided him and helped him grow. For him, ballroom is also a stage for creativity and self-expression: “It’s a celebration of who we are, what we’ve survived, and the beauty we bring into the world together.” Ballroom gave him the confidence to step into the real world, embrace his talents, and thrive in his career as an educator. “My Ninja family instilled in me the value of education and strong work skills, lessons that extend far beyond the ballroom floor.” These experiences shaped every part of his life, from personal relationships to professional growth, giving him the tools to succeed and the courage to be authentically himself.

As a protagonist myself in the Italian scene, I’ll now take the narrative licence to tell my own story and recount how ballroom culture arrived in and spread across Italy. I’m La B. Fujiko, and I began my ballroom journey in New York in 2008 with Javier, Benny, and Archie from the House of Ninja. Since then, I have traveled, practiced, walked and judged balls, met incredible people, built bonds, and worked to plant the seeds of a scene in Italy.

In 2011, I officially entered the House of Ninja and later became Mother of the Italian chapter. In 2019, I was honored with the titles of Pioneer and Legend.

In 2014, together with Dolores Ninja, I organized the first official Italian ball: The Italian Spring Ball. That night marked the true beginning of the Italian ballroom scene. Until then, voguing in Italy was mostly known as a dance technique, often misunderstood, and without the structure of Houses and categories. From that moment, many cities across the country began to develop their own scenes, and today Italy counts numerous events, balls, trainings, and Houses spread throughout the territory.

Through BBallroom, the organization I founded, I have hosted more than fifty events, combining balls, trainings, and workshops. One of the most important ones is The Scandalous Ball, which brings together more than a thousand people from across Europe and beyond every year in Milan. It is a night of true celebration of bodies, identities, and creativity. For me, every Scandalous Ball is a reminder of why we do this: because we need spaces where everyone can feel safe, powerful, and beautiful. The next edition will be held in Milan on November 15th at District272, marking the 10th anniversary of this ball.

Alongside the balls, Milan also hosts Milan Is Burning, a gathering created for the community to come together without the pressure of competition. It is a moment of care and exchange, a space for newcomers to practice, experiment, and find their voice. Unlike a ball, where categories and trophies dominate, Milan Is Burning is about joy, sharing, and reminding ourselves that ballroom is, above all, a community.

Over time, collaborations with artists, brands, and even mainstream platforms have allowed us to spread ballroom culture further, while keeping its radical roots alive. I strongly believe that ballroom must always remain a political act, not just a performance: a place where we fight against homophobia, transphobia, racism, and sexism by celebrating ourselves.

T’ai Ninja, from Milan, recalls: “I started in 2017 in Milan, I was taking voguing classes with my mother La B. Fujiko and she introduced me to ballroom. Ballroom is a space where I’ve been able to find myself in a way that I could have never done anywhere else. I discovered parts of my personality that were completely hidden and it has definitely changed my life.” She adds: “Ballroom helped my personal life by teaching me to feel comfortable in my own skin. It made me confident and proud of who I am, and it also gave me an amazing community of people that support each other.” Her categories, Body, Face, and Sex Siren, became tools of transformation: “It really takes confidence and courage to walk them. It has helped me see myself with new eyes. My House is my chosen family and the reason why I can walk proud today. I started my journey with Mother La B. Fujiko, and she guided me through this whole path.”

Saida Ninja, from Bergamo, explains: “Ballroom is my second life. I’m a professional dancer too, and I live these two ways at the same time. Ballroom helped me to be stronger in real life, helped me with my self-esteem, and gave me people I can support, helping them to feel safe and strong as well.” Her category, Runway, is a declaration of identity: “Runway for me, beyond the dress and the gorgeousness, is a claim, a moment where those who watch me can understand that I’m strong not only for the ballroom or the battle, but for myself, my persona, and for all women.”

Lyo Ninja, from Padua, adds: “I joined the House of Ninja at 17, and for me it means home and devotion. The first people who believed in me, who pushed me and loved me for who I was. Having a strong and recognized name today means being able to give back light and energy to something that once gave that to me, an equal exchange born from love and respect. To guide and raise new people will surely be both an act of demonstration and a way to represent this legacy.” As he grew up, ballroom became his true home, because it made him feel good and safe, while in his small hometown he was called virus for being gay, bullied, and at times physically attacked. For him, ballroom is freedom: “For me, ballroom means being able to bring out my most intimate and sexy side, knowing it’s not ridiculed or judged, but recognized as a powerful and distinctive trait.”

Sattva Ninja, from the UK and Germany, explains how ballroom became a natural part of life: “At this point it has become second nature to me. I love it and dislike it sometimes as well. When you’ve been in it for so long, having grown up with it from 15 or 16 years old for over a decade, you’ve seen so much. It is family, it is conflict, it is art, it is survival.” Her categories, New Way and Arms Control, embody this tension: discipline and fragility, creation and endurance. Ballroom helped her find peace with a broken family, as well as love and support in life. It even opened career opportunities she had never expected or planned. “Ninja has always been my house, the one that accepts me and my craft wholeheartedly. It is where I am allowed to grow and to be.”

From New York to Milan, ballroom has traveled far. The years have passed and the places are very different, yet its essence remains unchanged: turning marginalization into art, precarity into community, and pain into beauty. “Some of them don’t eat, they sleep under the piers, and they steal something to wear for one night to live the fantasy,” said Pepper LaBeija. Today, that fantasy continues to live and regenerate in every ball, in every pose, in every dip that becomes a declaration of life. Ballroom is not entertainment, it is collective resistance, an alliance of bodies that claim the right to exist.