Masculinity is a complex issue, shaped by an interplay of historical, cultural and social factors that have created limiting and distorted stereotypes. In popular culture, social expectations have helped to create images that still influence how Black men are perceived, both within their community and in wider society.

We decided to publish this intimate and delicate issue to explore the roots of the stereotypes in which many Black men still find themselves trapped today.

1. A Love Letter to My Brothers

by Naomi Kelechi Di Meo

To the boys I grew up with, and the men you’ve become—

This is a letter I’ve been writing in my head for years. Maybe since we were kids, all of us moving through the world without the language to name what was happening to us. Back when you’d race bikes down cracked sidewalks, shout across schoolyards, disappear into music or football or silence. I didn’t have the words then, but I see now what we were surviving. What you were being shaped into.

You’ve always been taught to hold something in. To stiffen. To perform. Even before your voices dropped or your shoulders widened, the world had already decided what kind of man you were supposed to become. Tough. Fearless. Useful. Controlled. I watched those expectations form around you like armor—sometimes handed down by family, sometimes forced on you by strangers who feared what they never cared to understand.

And let’s be clear: this performance didn’t begin in your generation. The monstering of Black masculinity has a long lineage—one written through plantation records, colonial propaganda, mugshots, music videos, and locker room jokes. It’s in the myth of the hypersexual predator, the absentee father, the brute strength without tenderness. It’s in the way your bodies are read before your words. It’s in how both white fear and Black respectability politics conspire to make you shrink or overperform. Too soft? You’re weak. Too angry? You’re dangerous. Too silent? You’re unreadable.

This is the tightrope you’ve always walked—required to prove your manhood in order to survive, but punished the moment you do.

And yet, I saw something else in you.

I saw you laugh with your whole body and then go quiet when vulnerability showed up. I saw the way affection got replaced by banter, how pain turned into jokes, how fear became rage or silence. And I want to say: I saw all of it. I see you.

Because behind that armor is someone who never really had the space to ask: What kind of man do I want to be? Instead, you were told what to avoid—don’t cry, don’t flinch, don’t talk too much about feelings. Learn to endure. Learn to deflect. Learn to carry.

And you did.

Sometimes at the cost of closeness. Sometimes at the cost of yourself.

I've seen the toll it takes—the mask that cracks in the late-night texts, the punchlines hiding grief, the fathers who taught you silence, the friend groups where softness is still mistaken for weakness. I’ve seen you try to be everything for everyone. Seen you reach for intimacy but flinch when it comes too close. Seen you disappear into work, into performance, into trying to “man up” just enough to be respected, but not so much you become the very stereotype they expect.

And I know: some of that survival was never yours to choose.

I’m not writing this to ask you to be different. I’m writing this because I love you. Not romantically. But as a sister, a witness, a fellow traveler. I love you in the way that wants you to live with your full chest. I love you enough to say: you were never meant to be only strong. That’s the lie.

This letter is a beginning. A mirror and a hand held out.

What would it look like to lay the armor down? What would it feel like to speak before being spoken about? To be held in your full complexity—not just by partners, but by brothers, by friends, by yourself?

Because beneath everything—the noise, the pressure, the code-switching, the masks—I still see that boy from the block, the classroom, the studio, the group chat. The one who wanted to be seen, not just expected. The one who needed room to feel. The one who deserved, from the very beginning, to just be.

So this is a love letter. And a soft rebellion.

You are allowed to be everything you are.

And I’ll be right here, listening.

—N.

2. The Masculinity of the Black Man: Fatherhood, Identity and Cultural Representation

by Maïmouna Gueye

In his film Get Out, Jordan Peele reflects on the persistence of racial stereotypes and biological racism towards Black men in the United States. The Black body is portrayed as having inherent qualities and a supposed “racial strength”, characteristics that are rooted in a long history of discrimination. The simplification of African American identity, which is denounced in the film, is not only an archaic phenomenon, but also persists in contemporary society.

This construction is rooted in a history of oppression. Supported by science for over two centuries, the racialisation of the Black body helped to legitimise slavery and then colonisation, providing pseudo-scientific justifications for subordination and exploitation. Even today, in the post-colonial era, the consequences are evident in the stigmatisation and structural discrimination affecting men.

Masculinity is a complex issue, shaped by an interplay of historical, cultural and social factors that have created limiting and distorted stereotypes. In popular culture, social expectations have helped to create images that still influence how Black men are perceived, both within their community and in wider society.

During the Atlantic slave trade, Black men were dehumanised and reduced to mere tools of labour. Their physical strength was emphasised to justify their exploitation, while their humanity was denied. Even after slavery was abolished, racist propaganda continued to portray Black men as threatening, aggressive and prone to violence, especially towards white women. This has been used to justify centuries of oppression, lynchings and social exclusion. In the 20th century, new challenges emerged: the need to conform to the models of masculinity imposed by white society in order to be accepted, and the need to reassert one's own identity.

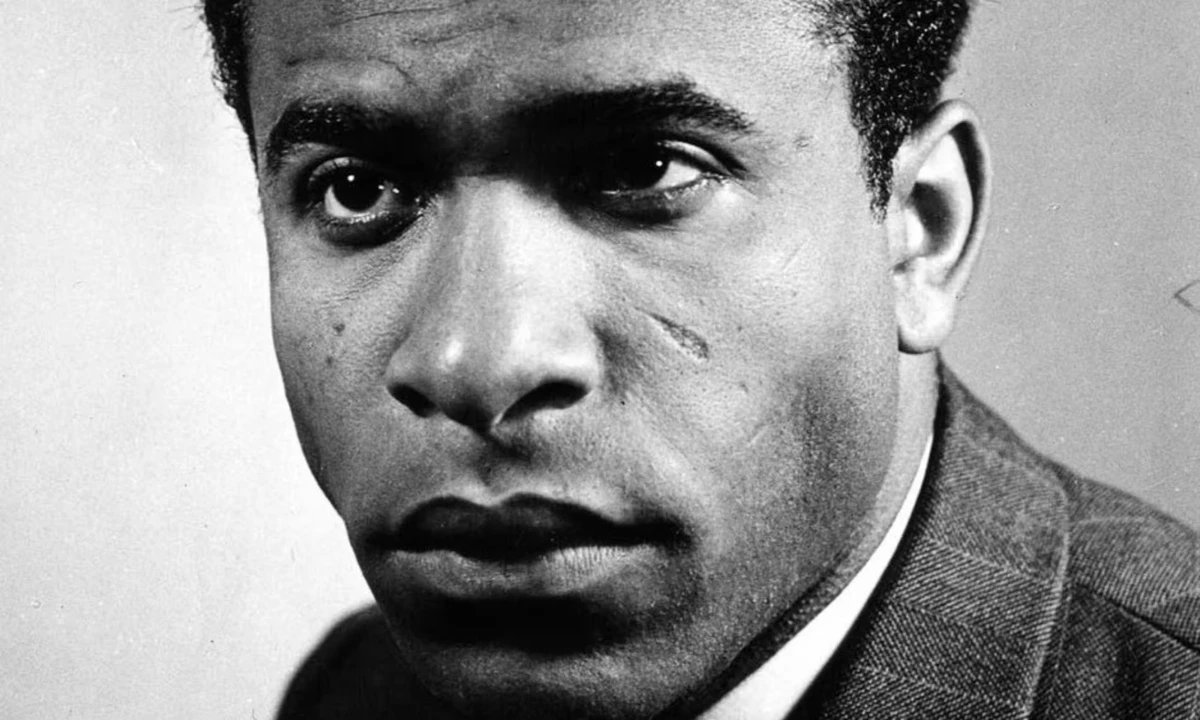

In Black Skin, White Masks, Frantz Fanon accurately describes this experience: «My body was given back to me sprawled out, distorted, recolored [...]. The Negro is an animal, the Negro is bad, the Negro is mean, the Negro is ugly»[1]. This perception is the filter through which Western societies have always seen Black men, reducing them to mere archetypes.

The rise of the Hollywood film industry and the globalisation of US culture consolidated this image, giving rise to a series of powerful and enduring stereotypes. In existing literature, works such as Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, albeit with abolitionist intentions, depicted African Americans as naive, docile, childlike beings to be protected.

After gaining the right to vote and citizenship following the Civil War, African Americans began to be perceived as dangerous. The myth of “Black brutality” emerged, portraying African Americans as a threat to the purity of white women and, more broadly, to white society. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Great Migration further fuelled fear of African Americans, particularly among the white working classes who saw them as competitors in the world of work.

These representations had deep effects: on the one hand, they diminished the individuality of African-Americans; on the other hand, they fuelled racist attitudes spread through popular culture. The image of Black men that has been built across centuries is still today an invisible cage that continues to influence social and cultural dynamics all over the world.

Black Masculinity in Pop Culture

The representation of masculinity in popular culture has often been trapped in rigid and limiting stereotypes, oscillating between images of brutal strength and narratives of absence and irresponsibility. Built on a long history of oppression and discrimination, these models have helped to define the identity of Black men in Western societies, influencing both external and internal perceptions within the African-American community.

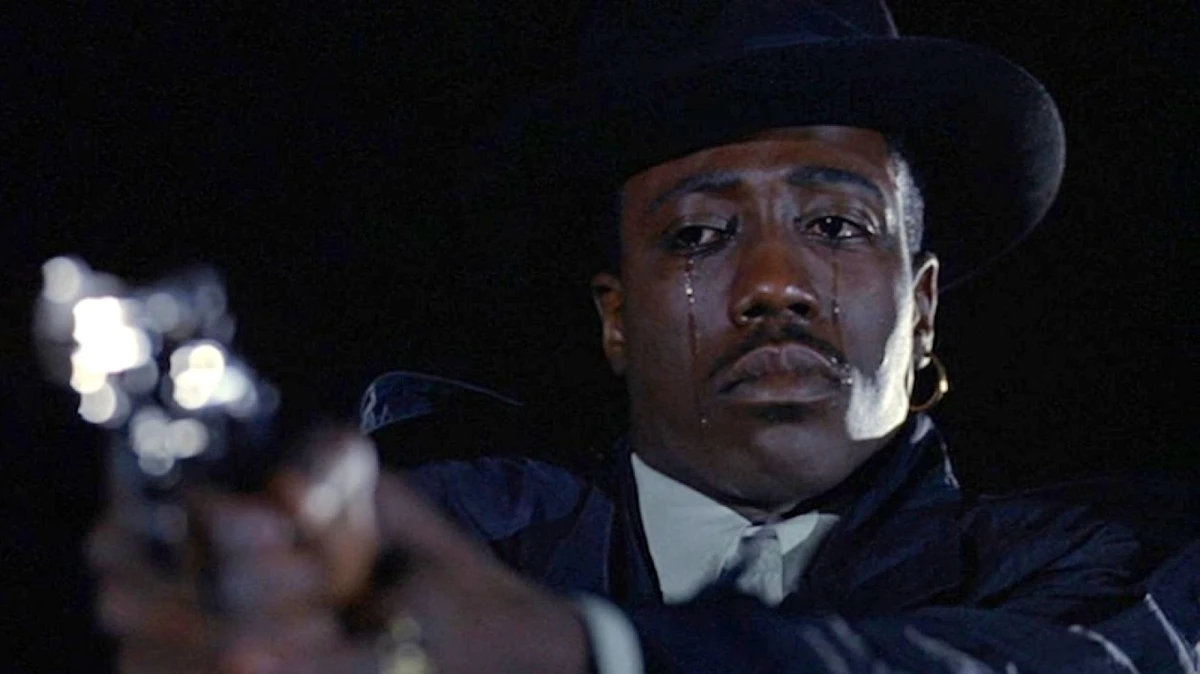

Over time, film and the media have disseminated often monolithic images of Black masculinity. One of the most common archetypes is that of the criminal: a violent Black man, often associated with gangs and drug trafficking. This stereotype was fuelled by the socio-economic conditions of urban African-American communities and exacerbated by the War on Drugs in the 1980s and repressive policies that contributed to prison overcrowding. Films such as New Jack City (1991) and Menace II Society (1993) explored this reality, attempting to expose its structural causes.

In Menace II Society, Caine Lawson (Tyrin Turner) grows up in South Central, Los Angeles, immersed in violence and crime. His father is a drug dealer who teaches him only about brutality and the drug trade, while his drug-addicted mother is unable to care for him. Following the deaths of both parents, he is placed in the care of his grandparents and taken under the wing of Pernell (Larenz Tate), a criminal who teaches him how to survive on the streets.

The Hughes brothers' film is not just another gang story. There are no Crips or Bloods, no turf wars or initiation rites. Instead, it shows how violence has become an inevitable part of life for many young African Americans. It is about pride, petty trafficking, and “an eye for an eye”.

One of the most controversial aspects of the film is its radical pessimism. Menace II Society is more nihilistic than other films in the same genre: it offers no real way out. Caine is unable to escape, not because he doesn't want to change, but because he is constantly sucked into violence by his surroundings. His fate is determined not only by his own actions, but also by a system that perpetuates crime and despair.

Through its brutal and realistic portrayal, the film highlights how the dream of a better life for many young African Americans is stifled by an apparently impossible-to-break cycle of violence.

The Evolution of the Father Figure in the Representation of Black Masculinity

The absent father is one of the most ingrained stereotypes in Black narratives. The cinema and media often portray African American men as incapable of taking on family responsibilities, fuelling the myth of a community without paternal guidance. This image has been reinforced by discriminatory policies such as the war on drugs and the US prison system, which have led to disproportionately high incarceration rates among Black men, thereby depriving entire generations of a father's presence.

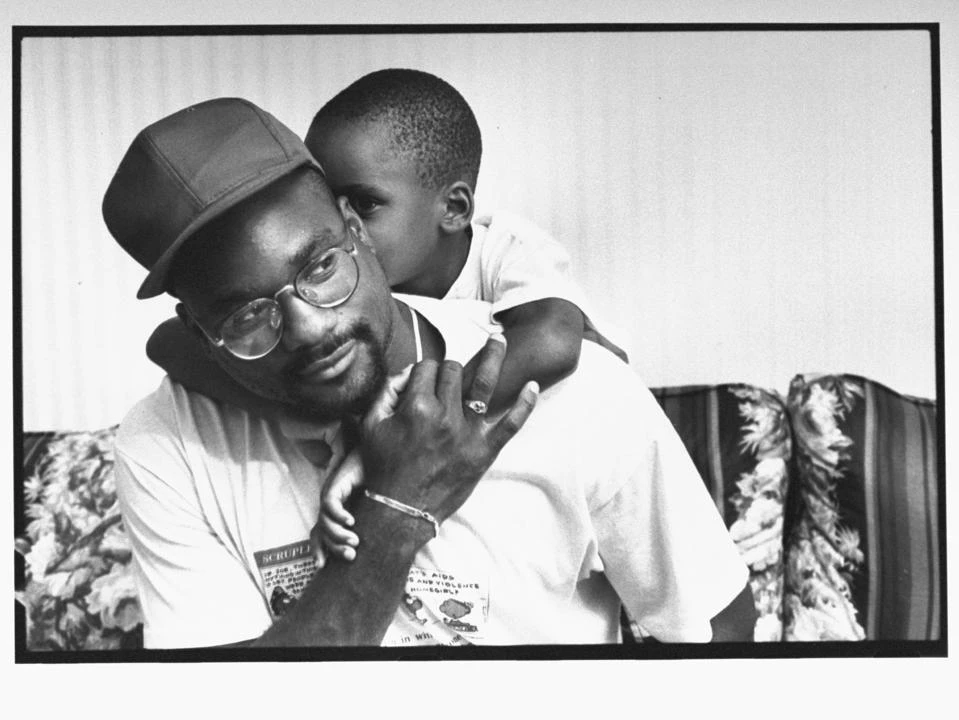

However, cinema has also attempted to challenge this narrative by offering more nuanced portrayals of Black fatherhood. A notable example is Furious Styles, played by Laurence Fishburne in Boyz n the Hood (1991). Furious is portrayed as a strong and authoritative father who tries to guide his son away from the violence of South Central by teaching him the value of responsibility and social awareness. His presence in the film challenges the idea of the absent father and demonstrates that there are Black men committed to guiding their children.

This evolution reflects a broader cultural shift, moving from two-dimensional and stereotypical portrayals to a more balanced and authentic vision. Contemporary films not only challenge imposed models, but also offer new perspectives on fatherhood, portraying men as loving, present and vulnerable.

This shift is crucial in overcoming toxic narratives and providing younger generations with more realistic and positive images, which can help to redefine the concept of masculinity in African-American culture.

Redefining Black Masculinity Through Culture

Social expectations often impose rigid views of men, particularly Black men, who are forced to conform to models of strength, dominance and resilience. However, popular culture, particularly film and literature, has the power to effect change by offering more authentic and multifaceted representations.

Identity is not monolithic; it encompasses strength, vulnerability and fragility, as well as a constant search for self. Stories that explore these dimensions are necessary to enhance the diversity of lived experiences, and cinema is a medium that can facilitate this.

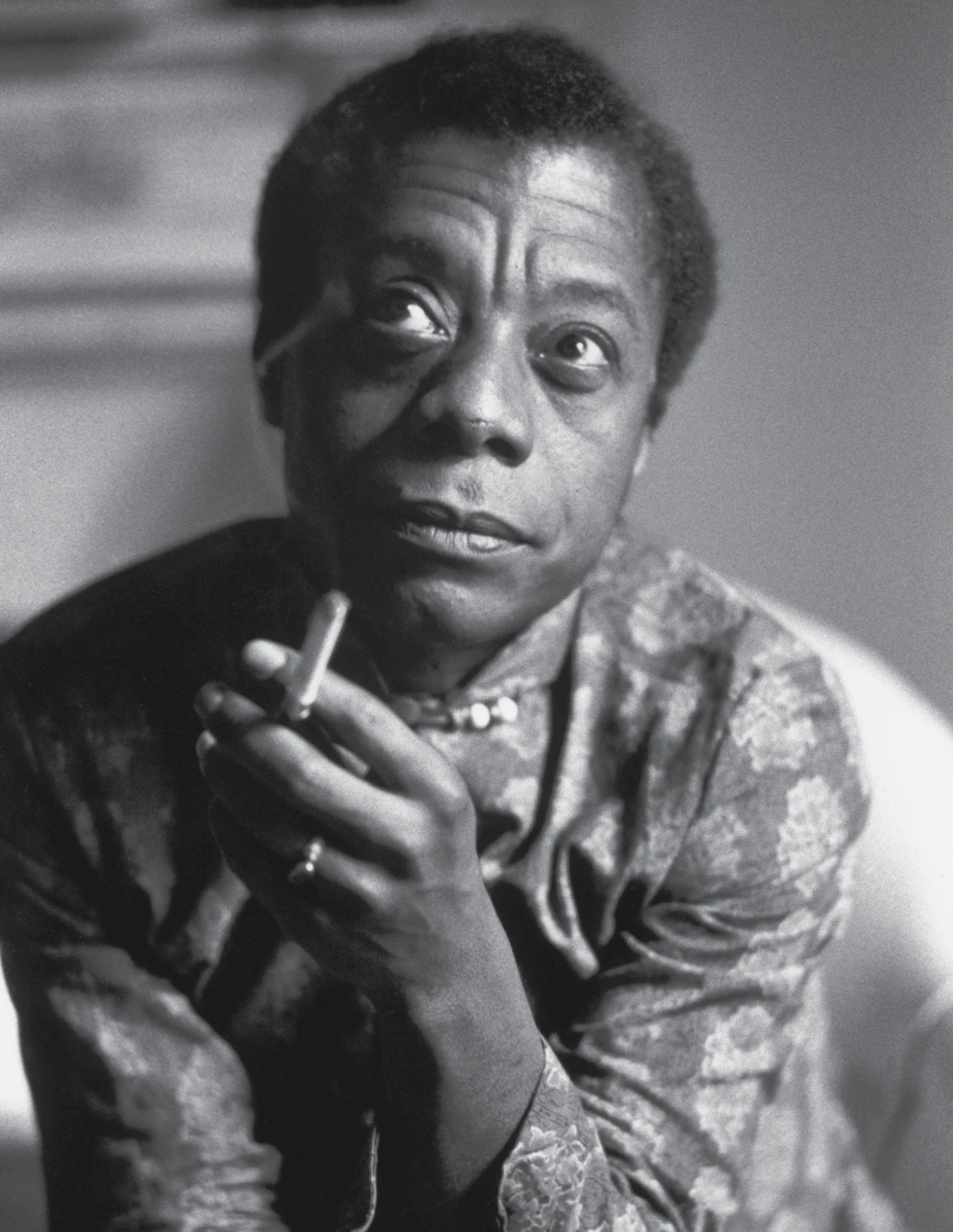

James Baldwin played a crucial role in this movement by challenging rigid and violent models. Through his works, he proposed a vision of masculinity that included empathy, love and vulnerability — elements that were often absent from traditional representations. This vision paved the way for a more complex and humane narrative.

Barry Jenkins' film Moonlight perfectly embodies this Baldwinian vision. Through the story of Chiron, it explores the challenges of identity and sexuality within a social context that enforces aggressive masculinity. Juan, played by Mahershala Ali, offers an alternative model of fatherhood, providing emotional guidance rather than repressive authority. Moonlight not only challenges Hollywood stereotypes, but also fits into the tradition of the Black Arts Movement by celebrating Black identity and artistic expression. The film manages to balance an intimate and universal narrative enriched with African-American and queer cultural references, creating a bridge between communities and a wider audience.

Similar themes are explored in other films, such as If Beale Street Could Talk (also directed by Barry Jenkins) and RaMell Ross's Nickel Boys, which focus on African American experiences with sensitivity, prioritising the humanity of the characters. These films address real and current issues such as racial justice and mass incarceration, offering an alternative lens that values love, tenderness and resilience. While the denunciation of racism is present, it does not obscure the emotional depth and luminosity of the characters. These films offer a portrayal that challenges clichés and celebrates the complexity of the African-American experience.

Redefining masculinity beyond stereotypical representations is crucial to enhance the diversity of Black men’s experiences. Through film, Black directors are helping to create a more inclusive and conscious imagery, which celebrates the complexity of Black identity.

Promoting a more authentic representation not only enriches culture, but also invites society to reconsider its expectations and prejudices. In a world where masculinity is often defined by limiting stereotypes, cinema becomes a powerful tool for opening a dialogue and building a future in which diversity is recognised and celebrated. By telling stories that explore the strength, vulnerability and humanity of Black men, contemporary cinema is redefining what it means to be a Black man today, offering a more inclusive and authentic portrayal.

Notes:

[1] Fanon, F. (2008). Black Skin, White Masks (R. Philcox, Trans.). Grove Press. (Original work published 1952)

3. How Black Men Lose their Smile

by Murphy Tomadin

From the very beginning, every relationship, encounter, spoken sentence and observed behaviour shapes what is considered right, wrong, worthy, opportune. Nothing exists a priori, everything exists in the stories and meanings created between people. This includes what it means to be a man and what it means to be a Black man. When combined, these two identities represent the pinnacle of perceived violence: one grows up aware of being a threat. You learn early on that it is better to keep your head down because the voice that comes out of that body is unwanted, worthless and inferior. The first seeds of anger are sown: it grows fecundly, dancing alongside the inherently colonial expectations of strength and resistance.

I wished to tell you that I love you, you looked at me and words vanished, I remained silent, my guts were screaming inside, my neck stiffened when you stroked me and told me you loved me. They didn't stroke me, a hand on my cheek always had a stronger impact; the palm in the open air that went straight down to my left cheek. I wanted to cry, but it was forbidden. I swallowed all those tears, one step away from shattering like pottery on the floor. Now, those tears have become stalactites inside my caves. Screams rumble alongside all this melanin, I wanted to get rid of it, “May I come in?”, “No, Black people can't come in here”. I'm strong; I padlocked the door — you won't get in. I am a man.

When it comes to Black men, the concept of masculinity makes its way within the meanderings of mind and spirit as the necessity to adhere to an imagery of impenetrability, suffering is a concept that must be kept at distance as much as possible. Fear is not allowed.

I’m afraid, but in movies men are never afraid. Black men die fearlessly.

In narratives, the concept of trauma is often linked to a single event that is defined as traumatic. The way historical events are passed down from generation to generation is often overlooked, if not dismissed. Black men who were subjugated, whose sexuality was defined as animalistic and whose existence was considered inferior. Navigating such an environment changes the whole body and the way it responds to danger. The myth of strength creeps in, stiffens and calcifies, suppressing the possibility of knowing, reading and understanding oneself in the first place. This mechanism is then passed down from father to son.

You ask me how I feel, I don’t have the vocabulary, the words to answer to you, I should feel alive, and yet I feel so empty. My thoughts are overlapping in my head, and you ask me how I feel. But how would I know? I just want to run away, I can't answer that question, I'm not trained for this, No one has ever asked me that before, well, maybe someone has, but I've always answered, “Fine, and you?”, there's no time for these questions, there are serious things to do. How far do I have to go to find the answers to your questions? I am a man. Where are you taking me with this question of yours? What do you want to see when you stare right into my eyes? My heart is pounding in my chest. I just want to leave. Your request for closeness tears me in two, I gather myself together and push everything back in. I have to go.

The hyper-sexualization of Black man’s body is a sticky resin expanding through the mind, as a standard that you cannot avoid, otherwise you are not a man at all. The real magic of colonialism is that you no longer need white bodies to make certain statements true, they have become sedimented and shared, they have turned into concrete matters and concepts that are accepted as truth by the very people who have suffered the consequences.

How many women, how many centimeters, everything has to be quantifiable. I didn’t really like her, but the others were pushing from behind with their shoulders and giving me pats and stifled laughter. “Now I'll show you who I am”. Why aren't you working now? Please. What a terrible impression I’ll make! What will they say about me? I hate myself. I hate everything about myself. Why can't I be normal? She looks at me as though I were an animal in a zoo cage and asks me if it is true what they say about Black people. I can't wait for it all to be over. The truth is that I can't hear anything,I have become deaf and blind to myself. Perhaps it's simply too risky to listen.

The dimensions of doing and being become blurred and intertwined until the former takes precedence over the latter. Doing becomes being, the need to prove one's worth through doing takes root in the mind, looking at oneself through the eyes of others is the story of the Black body being treated as a tool for, an useful object. A Black man must prove that he can do something; otherwise, is he really a man? What use is he if he cannot prove his ability?

Look at me, Daddy. Be proud of me. Am I strong enough?

«When a society is not equipped to hold up an accurate mirror to us, we end up interpreting our reflection according to the available structures and terminologies»[1].

When I look in the mirror, everything looks wrong, my legs are shrunken and my biceps are thin. They say my hair looks like a sponge, perhaps they want me to cleanse their racist consciences. I try throwing a couple of slashes in the air, I want to cut it as though I have katanas attached to my shoulders. How can I earn respect? I wish someone had explained to me earlier that, like the best illusionists, I had managed to turn contempt for myself into hatred and ferocity towards women. I treated them as objects and did not know how to love myself. Perhaps nothing disappears or dissolves into nothingness, I guess everything is transformed. I treated you as an object because I could not see myself as a person in the first place. I pushed you away because I could not approach myself. An obedient servant to the ideal man. Chained and alone, trying to understand what strength meant, looking for feelings with my eyes closed in a fog of cigarettes, with alcohol in my veins to fuel silly evenings, making myself strong in a language that did not belong to me because I knew of no alternative. On my knees with my face in the toilet, I watched all my insecurities violently come out of my mouth, gasps and spasms which are the price I pay for not saying no to other men, I pay for my weakness dressed up as cowardly strength.

Grief becomes fossilised and entrenched, fuelled by a reluctance to share one's feelings. Intimacy is either considered the prerogative of female friendships, or equated with sexual intercourse. It is rarely considered to be on the same level as the process of getting to know oneself and others: this is the common but never explicitly stated rule within a group, as if black masculinity were an immutable monolith and there was no alternative way of acting but to suppress and silence.

If darkness falls, I won't have to hear any more. I can't bear all this noise inside. My face feels heavy, as though I am wearing a huge mask. I don't know how to heal these wounds, I look at my father, entrenched in his silences, what he taught me, I have never seen him cry. I see my female friends calling each other, they say they talk on the phone for hours, when they meet, they rest their heads on each other's legs, they trust each other and open up. I envy them in silence. I drink indifference and eat anger. This seems consistent with being a man to me. As if I can't express anything else, my anger is almost expected. I am a walking menace, I hate myself. I would like to hurt you one hundredth as much as you hurt me. My body is wrong everywhere. I only know this language. I wish I could melt into the embrace you tried to give me, but I pushed you away. You were one step away from that memory of me as a child, running towards the teacher after falling over, while everyone laughed and called me "weak", "queer", "sissy". I had to push you away by force. This is not how a man behaves. Either I'm a threat, or I’m the expectation of 25 centimeters, or I'm nothing. I've fallen to the bottom, it's so dark, I just wanted them to look into my eyes and recognise my existence. I want to disappear. Break into a thousand pieces. I have all the evil in my right fist that is thrown against the door. I'm breathing hard, my hand throbbing and swollen. Is this fist the words I cannot say? Black men are violent, they are beasts.

Peace and liberation are often used interchangeably. But they are not: one can be at peace even if they are not free. You can be at peace even if you are shackled. But a path to liberation must be conceived of, desired, imagined and practised. A possibility to consider the Black man as an individual whose identity is constructed also by the capacity to legitimise pain and to know oneself in order to expand the capacity to feel, moving beyond anger as the only socially accepted and expected response. Rethinking oneself outside of an ethics of domination as the only possible approach to navigating the world. Leaving aside the mask of dissimulation, breaking generational cycles of acted and suffered violence.

I want to allow myself to be whole, I don’t want to hide, I want to be able to feel. The truth is that I do feel, but I forgot where the volume switch was, because I often feel muted.

«Men need love. Men need love from other men, not just from women, or their partners. Men need intimate, non-sexual love; a love that goes beyond the expectations placed on their manhood. [..] The mask that men have worn for decades, even centuries, has to be fully removed for us to see the true face that lies beneath; once we remove it, we will see that what lies beneath is a reflection of our true selves, however we choose to be..»[2].

Notes:

[1] Mullan, J. (2023). Decolonizing therapy: Oppression, historical trauma, and politicizing your practice. WW Norton & Company.

[2] Bola, J. J., & Bola, J. J. (2019). Mask off: Masculinity redefined. Pluto Press.

References

Bibliography

Bola, J. J., & Bola, J. J. (2019). Mask off: Masculinity redefined. Pluto Press.

Mullan, J. (2023). Decolonizing therapy: Oppression, historical trauma, and politicizing your practice. WW Norton & Company.

Fanon, F. (1965/2018). Pelle nera, maschere bianche (L. Muraro, Trad.). Torino: Einaudi.

Donate

Donate